What ≪A Christmas Carol≫ Asks of Us Today: Returning to the Heart of Christmas

As Christmas draws near, our imaginations instinctively turn to familiar films, seasonal animations, and shelves lined with well-loved books. Among the many stories that have shaped our cultural memory of this season, few illuminate the essence of Christmas as clearly — or as persistently — as Charles Dickens’s ≪A Christmas Carol≫. It is no exaggeration to say that much of the modern vocabulary of “celebration” and “generosity” surrounding Christmas owes something to this small but luminous tale. In this month’s read.log, I return to Dickens not for nostalgia, but to ask why this old story still speaks with such clarity to our own age.

What We See Only When We Return to the Text

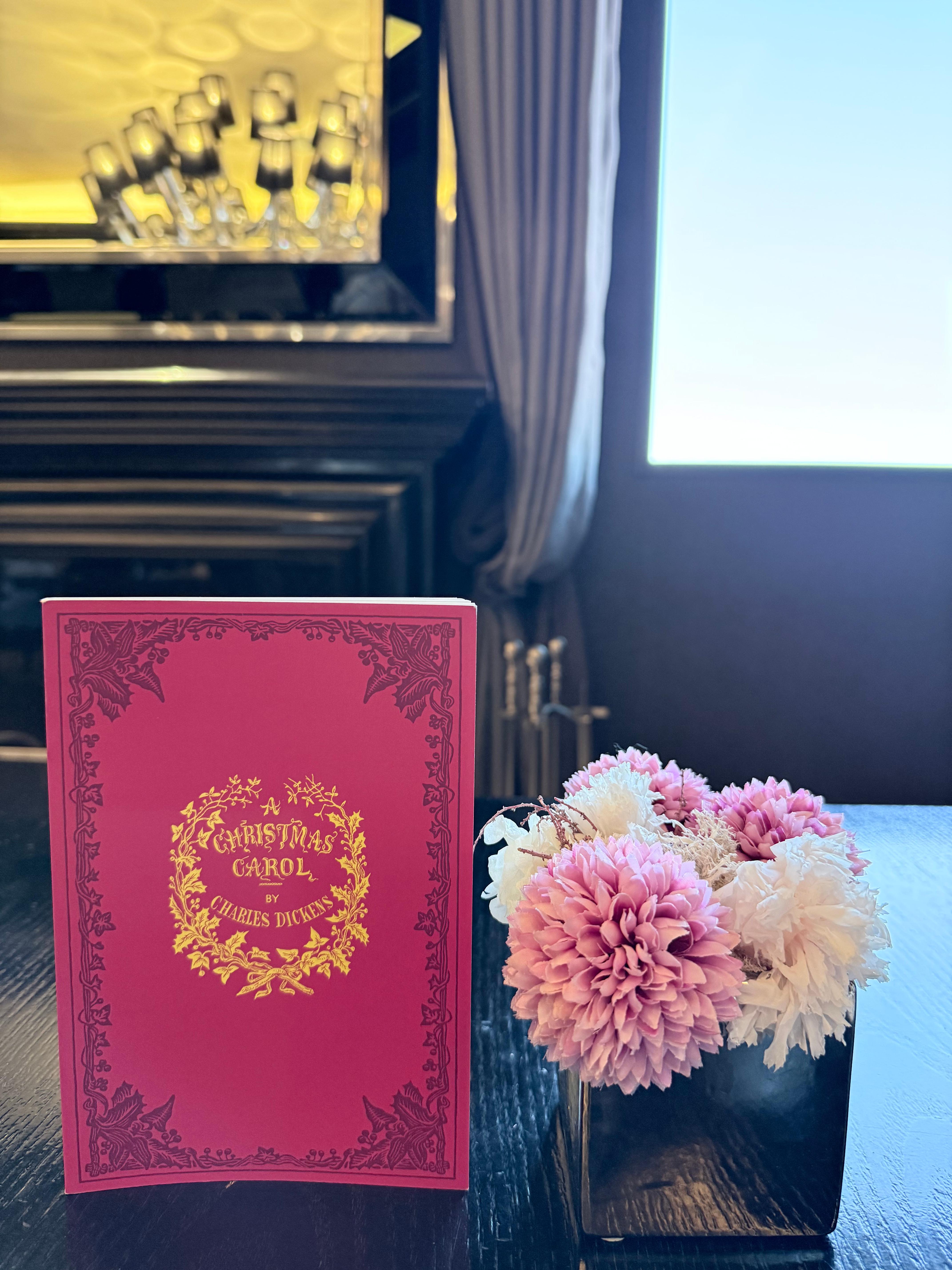

Because ≪A Christmas Carol≫ has been endlessly adapted, many of us first encountered it not in print but through a screen. My own earliest memory of the story came through the 2009 Disney film with Jim Carrey — an imaginative, if stylized, retelling. But no matter how many adaptations we watch, the true heart of the story lies in Dickens’s original words. And for this Advent season, I would urge you to read it — slowly, intentionally. There is something almost countercultural about holding the text in hand, especially a simple, accessible edition like the one published by <The Story>.

In a world of constant distraction, the quiet act of reading may be the most faithful way to listen to what Dickens actually meant to say.

A Story of First Love Lost

At the center of Dickens’s narrative stands Ebenezer Scrooge—a man who once loved Christmas with youthful abandon, but who, over the years, allowed cynicism to calcify around his heart. His decline calls to mind the church in Ephesus described in Revelation: steadfast in many ways, yet rebuked for having abandoned its first love. Scrooge did not lose his love through theological rigor or doctrinal vigilance, but the echo remains: the tragedy of a heart that forgets what it once cherished.

Then, one Christmas Eve, the ghost of Jacob Marley disturbs Scrooge’s carefully ordered isolation. Three more spirits soon follow, each unveiling what Scrooge has ignored: what he once had, what he presently refuses to see, and what he will inevitably reap if he continues on unchanged.

A Culture That Has Misplaced Christmas

Our contemporary problem may be deeper than losing the “spirit of Christmas.” Increasingly, we struggle to remember what Christmas is for. Amid year-end consumption and spectacle, the center of the season — the birth of Christ the Lord — is easily displaced.

In such a moment, ≪A Christmas Carol≫ functions not merely as a heartwarming story, but as a quiet theological provocation. It reminds us of what cannot be replaced without spiritual consequence.

Christmas marks the day God sent His Son into the world. Christ came to deliver us from our sin, to make us children of God, and to usher us into His kingdom. When that truth roots itself in us, “Christmas spirit” ceases to be sentiment; it becomes a life oriented toward grace. We remember the love God first extended to us, and we learn to extend that love to our families, our neighbors, and even those at the margins of our attention.

Three Paths of Restoration Dickens Offers Us Through Scrooge

Through Scrooge’s transformation, Dickens sketches three movements of recovery — movements every generation must rediscover.

1. Look back and recover your first love.

The Ghost of Christmas Past confronts Scrooge with the tenderness and joy he abandoned. Like the Ephesian church, we too must remember where love once burned brightly — our first love for Christ, and our first love for the people God placed in our lives.

2. See the neighbor before you in the present.

The Ghost of Christmas Present reveals what Scrooge refused to notice: the needs, burdens, and joys of real people around him. Love is never abstract. It is always embodied, always expressed in concrete acts of mercy. To see the present clearly is to discover how we might become someone’s answered prayer.

3. Remember the future that follows unrepentant living.

The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows the inevitable end of a life that remains closed, cold, and unresponsive. Revelation’s warning to Ephesus — “I will remove your lampstand” — comes to mind. Knowledge without obedience becomes judgment. And what is lost in the end is nothing less than the soul itself.

The Christmas We Need to Recover

So perhaps this Christmas is an invitation — not merely to celebration, but to examination. To open Dickens’s little book ≪A Christmas Carol≫ again is to allow oneself to be questioned. What have I forgotten? What have I neglected? What have I justified for too long?

If Scrooge could recover what he lost, perhaps we too may return to what is essential: the wonder of Christ’s coming, the grace that saves, and the love that moves outward into the world. In reclaiming this center, the joy and peace Scrooge tasted at the end of the story might echo in our own lives as well.

“May God, in His mercy, grant grace to each and every one of us.”

About Author

faith.log

A journal that connects faith and everyday life. In each small piece of writing, we share the grace of God and the depth of life together.